Summary: TriMV was detected in Colorado. Watch for stripe rust, viruses, fusarium head blight, root and crown rots, and fungal leaf diseases.

*Addendum: My group detected bacterial leaf streak disease in samples from Southeastern Colorado today. While this has not been a major problem in Colorado in the past, the disease has been re-emerging and may cause severe yield losses. Therefore, we are sending out an addendum to the most recent newsletter to make everyone aware of the disease.

Dr. Robyn Roberts

Field Crops Pathologist and CSU Assistant Professor Robyn.Roberts@colostate.edu* 970-491-8239

*Email is the best way to reach me

Introduction

Welcome to the 2024 growing season! I am excited to bring you the newsletters again, which will come out every 2 weeks. If you have pathology concerns, please don’t hesitate to reach out and/or send photos. The best way to reach me is by email: Robyn.Roberts@colostate.edu.

Disease Observations

Triticum mosaic virus:

Plants testing positive for Triticum mosaic virus (TriMV) were collected from Baca and Kit Carson counties (Figure 1). TriMV is transmitted by the wheat curl mite, and symptoms appear as yellow streaks and mosaic patterns on leaves. In the past, TriMV was typically found when co-infected with Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), but we have not yet detected any WSMV this year. We have observed an increasing number of TriMV-only positive samples over the past two years, so I encourage you all to stay vigilant in scouting and controlling volunteer wheat.

Management and prevention: There is no treatment for virus-infected plants, and no miticides are effective against the vector (the wheat curl mite). Controlling volunteer wheat and planting mite-resistant varieties are the best control measures. There is limited resistance available against TriMV, so controlling volunteer wheat between harvest and planting is critical.

Disease Watch and Management

Fusarium head blight (head scab)

The 2023 Field Season ended with significant Fusarium head blight (head scab, FHB). The fungal pathogen requires wet conditions, so FHB is more common after significant, prolonged rainfall, much like what we encountered in late May-early June last year. It prefers warm temperatures (~75-85°F), but under extended wet conditions the fungus can infect at cooler temperatures. The fungus infects flowers, so the timing of the wet, warm weather with flowering last year provided optimal conditions for disease development.

Symptoms of FHB include individual bleached spikelets on green heads, and pinkish-orange fungal spores may be visible on infected spikelets (Figure 2). The pathogen also produces a mycotoxin called deoxynivalenol (DON), which is a toxic chemical to people and livestock. Elevated levels of mycotoxin can accumulate even under minor disease conditions, and high numbers of damaged, wrinkled, or

‘tombstone’ grains can indicate high levels of mycotoxin. The spores produced from the initial infection can produce additional spores that infect other heads. Significant disease problems can therefore occur if wheat stands are uneven with late flowering tillers.

Infected corn or wheat residue can be a significant source of inoculum, and due to the high levels of FHB last year there is likely significant inoculum present in the environment to start disease this year. Managing residue and applying a fungicide that is labeled for FHB at early wheat flowering are the best control methods, in addition to genetic resistance.

Penn State University and colleagues at the Fusarium Scab Initiative have developed a risk assessment tool to predict the likelihood of FHB. I will be monitoring the site throughout the year, but you may also conduct your own risk assessment using their tool, available at: https://tinyurl.com/2jcvcze9. Colorado is currently in a low-risk category for disease development.

Root Rot and Crown Rot

FHB-infected seed from 2023 can also lead to root rot disease (Figure 3). Seeds infected with FHB may or may not show symptoms or signs of FHB but can still be infected. If infested seed is planted, root rot and crown rot may develop, as the fungus emerges and infects wheat plants directly from the seed. Prolonged drought stress coupled with high soil temperature in the fall promotes early disease development, so conditions last fall were favorable for disease. I encourage you to read more about Fusarium diseases in a recent University of Nebraska extension group article, which can be found here:

https://tinyurl.com/bdhvpjt9.

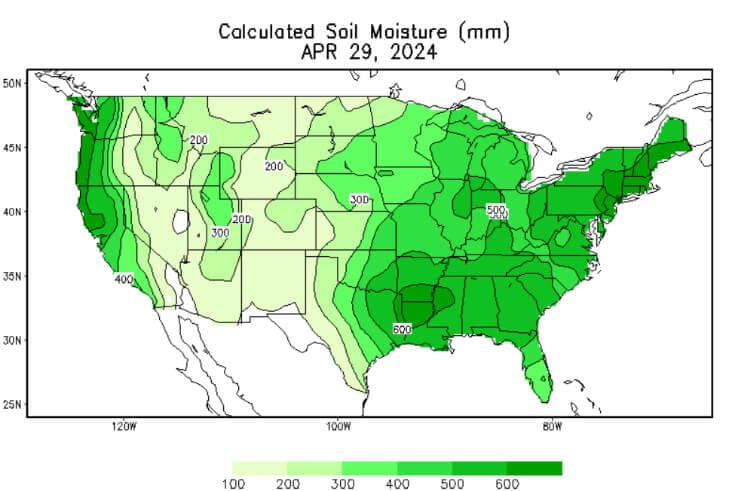

Stripe Rust

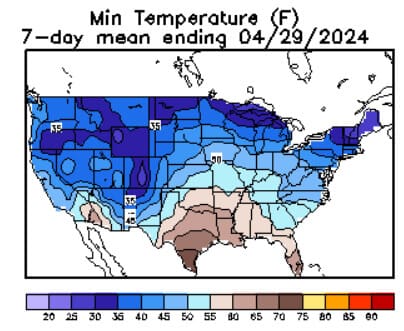

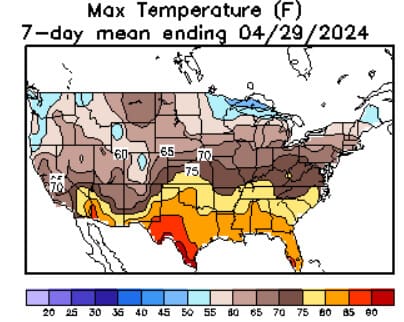

Scout for stripe rust (Figure 4). There are currently no reports of stripe rust in Colorado, but there is a fair amount being reported in Oklahoma and Texas. Stripe rust disease is dependent upon cool, wet weather, so stripe rust risk is greatest in the northeast counties that received recent rainfall and have had cooler weather. Stripe rust disease develops when temperatures are cooler (between 50-64°F) (Figure 5) and generally wet from intermittent rain or dew.

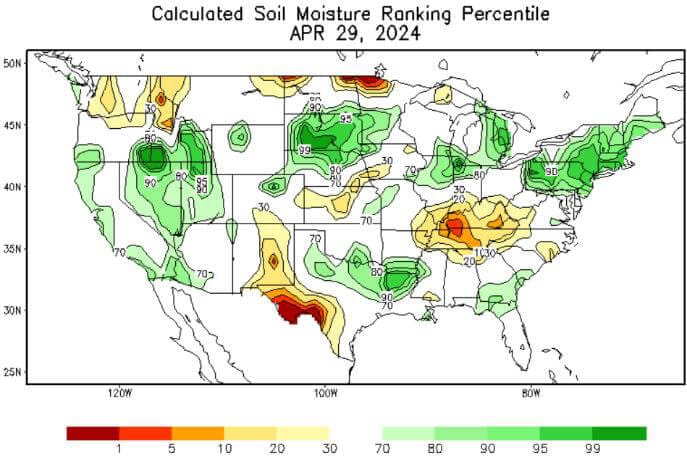

Soil moisture levels are often correlated with stripe rust incidence and can be used as a predictive tool in determining if stripe rust will emerge. This time of year, we look at the soil moisture levels in the south, particularly Texas and Oklahoma (Figure 6). Texas and Oklahoma have largely had sufficient rainfall to support stripe rust spore development, so it is possible that we will see stripe rust move in to Colorado in the coming weeks. This will depend on individual locations, though, as parts of the state have had more recent moisture, and other parts remain highly drought stressed. Importantly, soil moisture is only one predictive indicator of risk, and the disease is complicated. Once the disease is detected in Colorado, local weather conditions, varieties/resistance, and management practices will all drive disease development. We will continue to monitor for rust and provide recommendations as we reach critical growth stages. Please help us protect the efficacy of our fungicides and prevent fungicide resistance by carefully timing applications, following the label, and only when the disease pressure is appropriate. If you think you see symptoms, please feel free to send photos.

Figure 5. Temperature plays an important role in stripe rust disease development. The stripe rust pathogen requires both cooler temperatures and wet conditions to cause disease. States that have reported stripe rust (Texas and Oklahoma) have had temperatures conducive to disease development, and nighttime temperatures in Colorado are approaching optimal disease conditions for stripe rust development. Data from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center, https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/tanal/temp_analyses.php

Figure 6. Soil moisture levels are used as a predictive tool for stripe rust risk. Higher soil moisture levels are typically associated with higher stripe rust risk. We closely watch the southern states (Texas, Oklahoma) for soil moisture levels and the emergence of stripe rust as one tool to predict risk in Colorado. Left: Calculated soil moisture data (the total amount of water in an unsaturated soil), Right: Calculated Soil Moisture Ranking (compared to the historical average). Data from the National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center, https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/soilmst/w.shtml.

Viruses

We discovered that many of our samples in 2023 (and so far in 2024) have had very high levels of Triticum mosaic virus (TriMV), which is a closely related but different virus from Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV) (Figure 7). The resistance that works against WSMV does not work against TriMV. However, because TriMV is transmitted by the wheat curl mite like WSMV, using varieties that carry resistance against the mite could help curb TriMV.

Tan Spot and Stagonospora leaf blotch

Tan spot disease is caused by a fungus and can appear this time of year. However, the disease is dependent on wet conditions and the risk will vary by location. Stagonospora leaf blotch is also caused by a fungus, and symptoms develop in the spring and display small, yellow spots on lower leaves that develop into elongated, dark leaves as the season progresses. Wet, rainy weather, high humidity, and moderate temperatures (~68-75°F) favor disease development, and recent weather has been favorable for disease development in some areas. The fungus survives in infected residue. Typically, Stagonospora does not cause significant yield losses in Colorado, and is often found alongside tan spot disease (Figure 8).

Management and prevention: As long as the weather continues to get warmer, Stagonospora activity should decrease. Because the fungus survives in wheat residue, rotating crops will help reduce the number of spores in a field the following years. Fungicide seed treatments also help protect seedlings from infection.

Bacterial Leaf Streak Disease

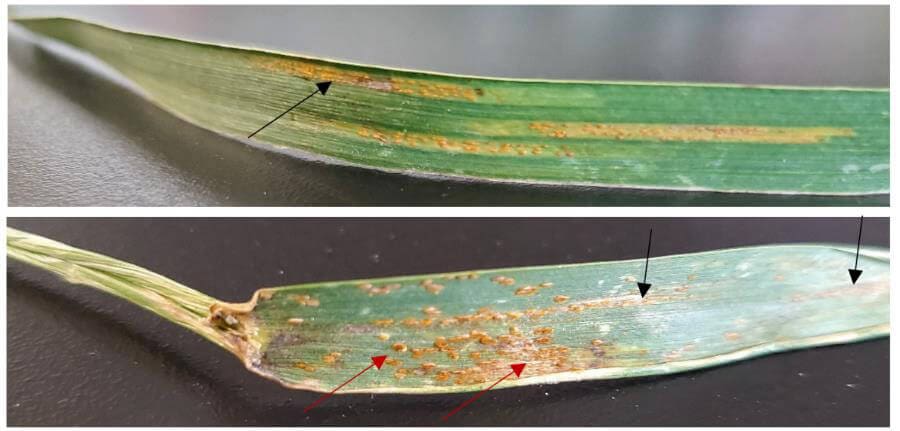

Bacterial leaf streak disease (BLS, caused by Xanthomonas translucens) was detected at the Plainsman Research Center in Baca County. BLS symptoms appear as water-soaked brown or yellow elongated lesions or spots that often follow leaf veins (Figure 1). BLS is a re-emerging disease in cereals, and has been showing up more often and in more severe cases across the Great Plains, especially in the midwest. Unfortunately, although the disease was initially discovered in the 1920s, there are still many unknowns about the environment it requires to develop disease, and how it is spread. It is likely spread long distance (miles) through rain events, and short distance (plant to plant) through rainsplash and dew. It is unknown if BLS is seed transmitted. Recently, yield losses of up to 60% have been reported in some cases. While this disease has not been a major issue for Colorado in the past, my research group has found that recent strains (‘isolates’), specifically from Colorado, are more aggressive than older isolates and can cause more severe disease, suggesting that the pathogen may be evolving/changing. It is important to scout your fields regularly to prevent spread.

Management and prevention: Unfortunately, there is no chemical or pesticide available to control BLS and no disease resistance. BLS is a re-emerging disease in the U.S., and my lab is currently studying the isolates collected in Colorado. The best management practices are to try to quarantine diseased areas as much as possible. This includes not moving equipment through these areas (or cleaning/disinfesting machinery thoroughly after use), and walking through these field areas last (it can probably spread on clothes). Be vigilant in scouting for BLS, and if you observe it please contact me.

Additional Resources

- Colorado Wheat Entomology Newsletter: https://coloradowheat.org/category/news-events/wheat-pest-and-disease-update/

- Fusarium risk tool:

https://www.wheatscab.psu.edu/?ct=YTo1OntzOjY6InNvdXJjZSI7YToyOntpOjA7czo1OiJlbWFpbCI7aToxO2k6NjM7fXM6NT oiZW1haWwiO2k6NjM7czo0OiJzdGF0IjtzOjIyOiI2NjA1OWYxMzk5MmJjMzY4ODcyMDIyIjtzOjQ6ImxlYWQiO3M6MjoiMjAiO 3M6NzoiY2hhbm5lbCI7YToxOntzOjU6ImVtYWlsIjtpOjYzO319 - Fusarium article, Uncommon Wheat Disease in the Nebraska Panhandle in 2023:

https://cropwatch.unl.edu/2024/uncommon-wheat-disease-nebraska-panhandle-

2023?utm_source=University+of+Nebraska-Lincoln+CropWatch&utm_campaign=41a18a2c0f-

EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_08_14_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d184080585-41a18a2c0f-137130681 - Information about the ‘green bridge’ and risks for viral diseases due to volunteer wheat:

https://eupdate.agronomy.ksu.edu/article_new/spring-emerged-volunteer-wheat-should-producers-worry-about-wheat-streak-mosaic-virus-and-the-green-bridge-436-4 - Fungicide Efficacy for Control of Wheat Diseases Table: https://cropprotectionnetwork.org/publications/fungicide-efficacy-for-control-of-wheat-diseases

CONTRIBUTORS: Many thanks to Sally Jones-Diamond, Zane Jenkins, Ron Meyer, Amber Pelon, and Dr. Esten Mason who contributed to this report.